The Best in Christian Thinking for the Common Good

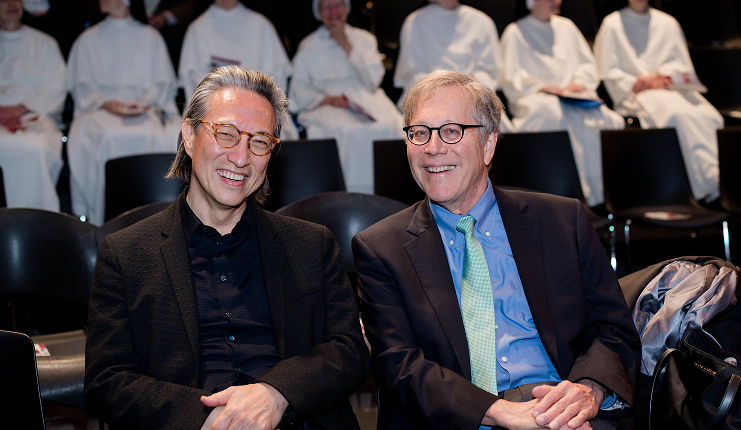

THE MICHAEL J. GERSON MEMORIAL PRIZE

On November 19, 2025, the Trinity Forum awarded the first annual Michael J. Gerson Memorial Prize for Excellence in Writing on Faith and Public Life. Learn more about Michael Gerson, the Prize, and the 2025 winner, Matthew Loftus.

FEATURED

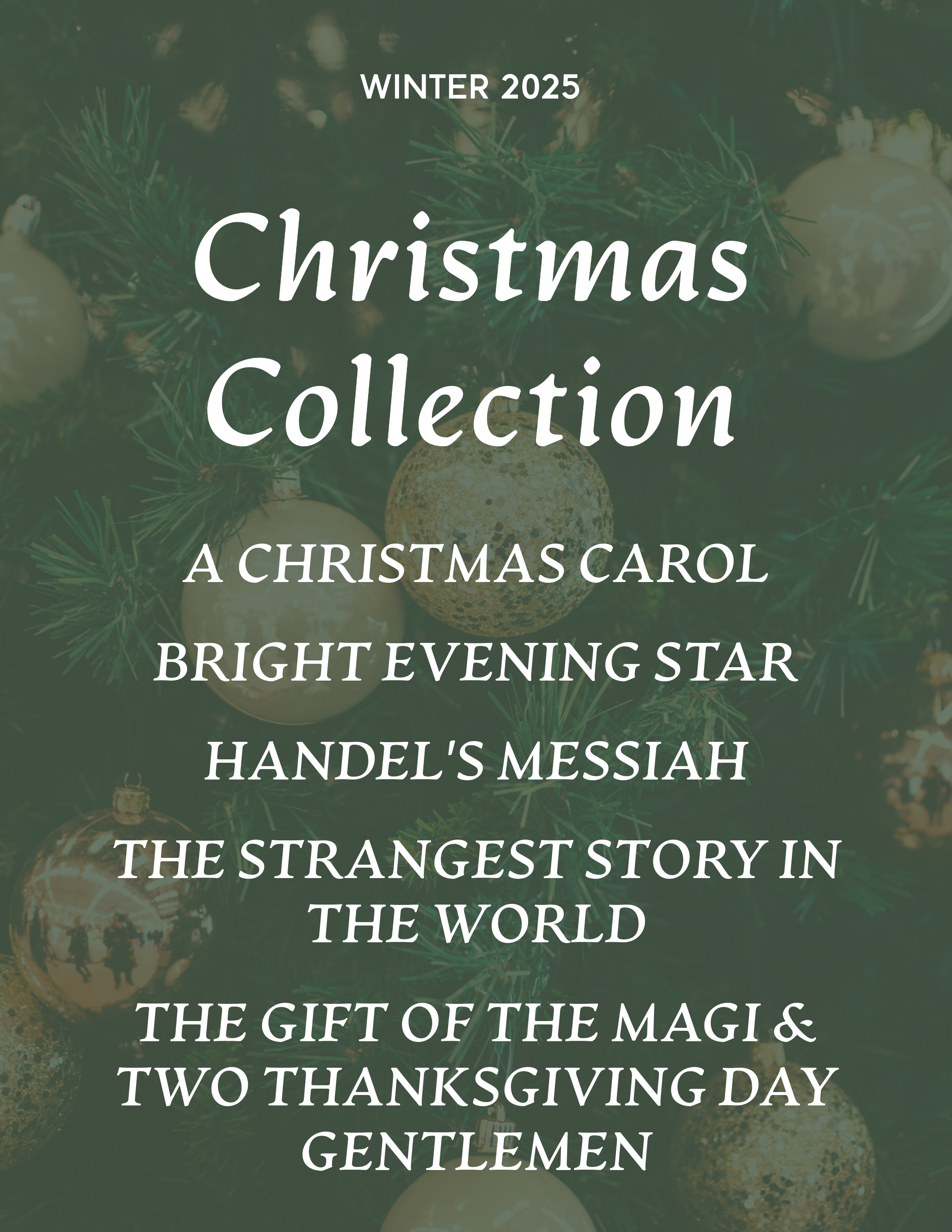

TRINITY FORUM READINGS

Bringing you the best of classic and contemporary literature and letters, introduced by today’s experts, and tailored for individual reflection and group discussion. Trinity Forum Society members receive quarterly Readings digitally or by mail. Browse our collection of over 100 Readings below.

TOPICS TO EXPLORE

Human Flourishing in a Digital Age

Engaging with Creation, Arts & Literature

Guided by Faith in the Public Square

Pursuing Spiritual and Character Formation

Upholding Human Dignity in Turbulent Times

Wisdom from Theology and History

Join the Trinity Forum Community

Learn More about Trinity Forum Membership

Learn how being part of our community can help you apply Christian wisdom to renew our culture today.