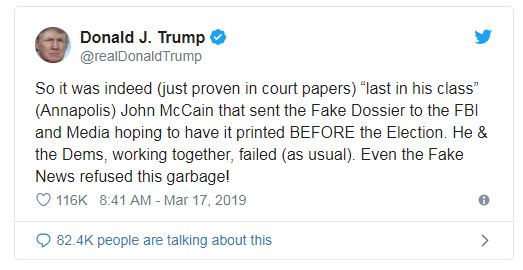

Donald Trump is not well. Over the weekend, he continued his weird obsession with a dead war hero. This time, his attacks on John McCain came two days after the anniversary of McCain’s release from a North Vietnamese prison camp. He tweeted this:

And this:

And retweeted this:

All of this comes in the aftermath of Trump’s comments about McCain in 2015. “He’s not a war hero,” Trump said. “He was a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.”

These grotesque attacks once again force us to grapple with a perennial question of the Trump era: How much attention should we pay to his tweets; and what exactly do they reveal about America’s 45th president?

I’m sympathetic to those who worry that too many Americans spend too much time paying too much attention to what Trump tweets. The danger is that we allow Trump to succeed in keeping us in a state of constant agitation and moral consternation, in ways that are unhealthy and even play to Trump’s advantage, allowing him to control the nation’s conversation.

But that view, which might apply in some circumstances, shouldn’t apply in all circumstances. The real danger in so desensitizing ourselves to Trump’s tweets is that we normalize deviant behavior and begin to accept what is unacceptable.

A culture lives or dies based on its allegiance to unwritten rules of conduct and unstated norms, on the signals sent about what kind of conduct constitutes good character and honor and what kind of conduct constitutes dishonor and corruption. Like each of us, our leaders are all too human, flawed and imperfect. But that reality can’t make us indifferent or cynical when it comes to holding those in authority to reasonable moral standards. After all, cultures are shaped by the words and deeds that leaders, including political leaders, validate or invalidate.

“To his equals he was condescending; to his inferiors kind; and to the dear object of his affections exemplarily tender,” Henry Lee said in his eulogy of George Washington. “Correct throughout, vice shuddered in his presence, and virtue always felt his fostering hand; the purity of his private character gave effulgence to his public virtues.”

But the other reason we should pay attention to the tweets and other comments by the president is that they are shafts of light that illuminate not only his damaged soul, but his disordered personality.

It doesn’t take a person with an advanced degree in psychology to see Trump’s narcissism and lack of empathy, his vindictiveness and pathological lying, his impulsivity and callousness, his inability to be guided by norms, or his shamelessness and dehumanization of those who do not abide his wishes. His condition is getting worse, not better—and there are now fewer people in the administration able to contain the president and act as a check on his worst impulses.

This constellation of characteristics would be worrisome in a banker or a high-school teacher, in an aircraft machinist or a warehouse manager, in a gas-station attendant or a truck driver. To have them define the personality of an American president is downright alarming.

Whether the worst scenarios come to pass or not is right now unknowable. But what we do know is that the president is a person who seems to draw energy and purpose from maliciousness and transgressive acts, from creating enmity among people of different races, religions, and backgrounds, and from attacking the weak, the honorable, and even the dead.

Donald Trump is not well, and as long as he is president, our nation is not safe.

Peter Wehner is a contributing editor at The Atlantic and a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He writes widely on political, cultural, religious, and national-security issues.